Shipping quote request

We’ll calculate the shipping price as soon as getting your request.

Shipping quote request

We’ll calculate the shipping price as soon as getting your request.

You May Also Like

More from this Dealer

Champs Elysées Etching by Dufza, Paris, 1940

André Masson - Original Lithograph 1964

Marc Chagall - The Bible - Boaz wakes up and sees Ruth - Original Lithograph 1960

Raoul Dufy - Chickens - Original Etching 1940

Woman - Original Photography Signed by Cyrille Druart 2018

Venus - Limoges Porcelain Blue and Gold 1967

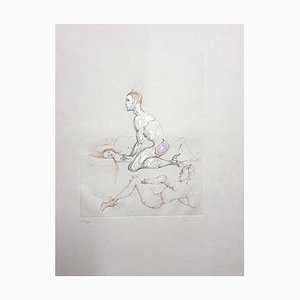

Voyeur Lithograph by Leonor Fini, 1982

Alfred Manessier - Maze - Original Lithograph 1954

Maurice Estève - Composition - Original Lithograph 1964

André Lanskoy - Composition - Mourlot Lithographic Poster 1960s

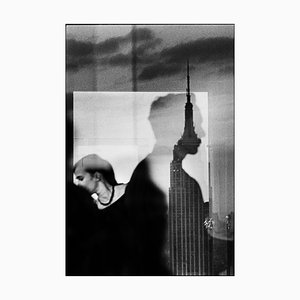

Original Photography Signed by Cyrille Druart 2019

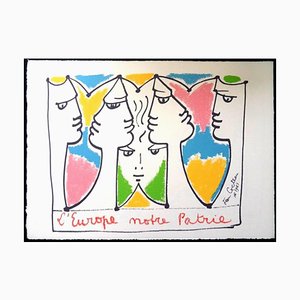

Jean Cocteau, Europe Bridge of Civilizations, Lithograph, 1961

Max Ernst - The Soldier - Original Lithograph 1972

André Minaux - Abandoned Boat - Original Lithograph 1964

Charles Lapicque (after) - Homage to Dufy - Lithograph 1965

Georges Braque - Original Lithograph 1963

after Salvador Dalí - Tienta en Espana - Lithograph 1983

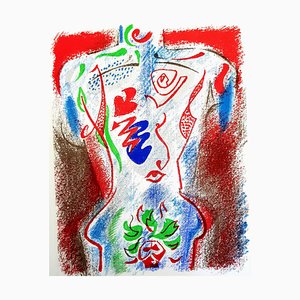

Jean Cocteau, Woman Portrait, 1959, Original Lithograph

Jean Bazaine (after) - Lithograph 1958

Jean Cocteau - Bulls - Original Lithograph 1965

More Products

Get in Touch

Make An Offer

We noticed you are new to Pamono!

Please accept the Terms & Conditions and Privacy Policy

Get in Touch

Make An Offer

Almost There!

To follow your conversation on the platform, please complete the registration. To proceed with your offer on the platform, please complete the registration.Successful

Thanks for your inquiry, someone from our team will be in touch shortly

If you are a Design Professional, please apply here to get the benefits of the Pamono Trade Program